This article originally appeared in Acres U.S.A.’s June 2025 issue. Reprinted with permission.

Many livestock producers have been seduced by the dogma that the path to profitability lies in avoiding soil inputs. The expectation is that grazing management alone will improve forage productivity, which will increase soil mineral availability over time, and that livestock genetics can be adapted to overcome imbalances in mineral nutrition in the interim to long term. With this mindset, it is common to supplement livestock with free-choice minerals to avoid any nutritional deficiencies that might be too detrimental to animal health and performance.

There are several problems with this paradigm, from my perspective.

Livestock Prefer Plants over Powders

Livestock prefer to eat forages over rock minerals. They will consume mineral powder when they are experiencing a nutritional deficiency, but only up to the point that they are no longer deficient. There can be a large gap between the mineral level that is sufficient for animals to survive and the mineral level animals require for optimal health.

This is similar to the discrepancies between the FDA’s Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) for nutrients and the levels needed for optimal health. The RDA (which Jerry Brunetti used to call Really Dumb Advice) for Vitamin D is 400 IU per day. But expose your skin to sunlight for 20 minutes and your body produces 20,000 IU in 20 minutes and then shuts off. Who do you think knows best — the FDA or our bodies’ designer? This is a gap of 50x between the supposed minimal level needed to survive and the optimal level needed to thrive.

When we rely on free-choice minerals, livestock will consume what they need to survive, but not necessarily what is needed to thrive.

Some Minerals Are Absent from Some Soils

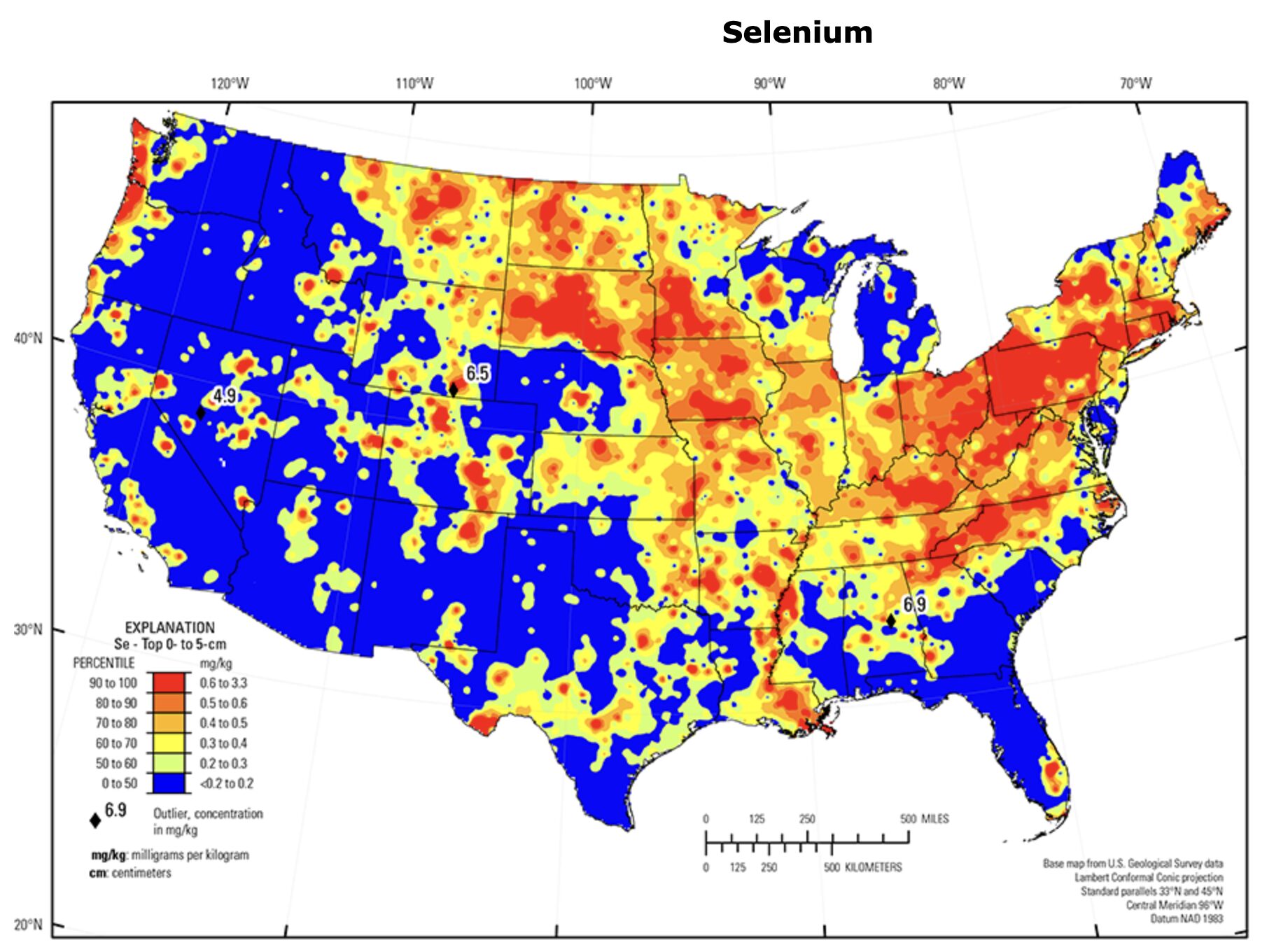

Some minerals are absent, or are present in too small of quantities, in some geological profiles, because of variations in parent bedrock, and because of weathering. There are geographic regions where you can have ideal grazing management and soil microbiome regeneration, and the forages will still be deficient in selenium, iodine, cobalt, molybdenum and possibly other minerals.

No matter how much you improve carbon cycling and soil health, it remains essential to address these minerals as soil amendments if you desire them to be present in your forages.

Supplementing Livestock Is the More Expensive Approach

In high-rainfall environments, with high forage productivity and a high carrying capacity, it is much less expensive to correct soil mineral imbalances than it is to supplement livestock. Selenium and iodine can be applied to soil for a fraction of the cost of supplementing livestock. The idea that we can free choice feed minerals as a pathway to remineralizing soils is the most expensive choice.

Let’s compare the relative merits of feeding livestock vs. feeding the soil by looking at two nutrients commonly given to cattle: selenium and iodine.

Selenium

The benefits of selenium in cattle are well-known, and it is considered essential to ensure livestock have adequate levels. Cows with adequate selenium levels don’t get mastitis—the most costly disease in dairy cows—and selenium injections can be used both to prevent and treat mastitis. Or, you can maintain adequate levels in your soils.

Most soils across the United States, particularly in the West and South, have inadequate levels of selenium. Soil applications of selenium are relatively inexpensive. When selenium is in the soil in a bioavailable form, it’s taken up by pasture and feed crops and is delivered directly to the cows in their food. This is not only much less expensive than selenium injections or selenium feed supplements — it’s also a foundational shift in farm economics. On the farm’s balance sheet, selenium moves from being a continual operating expense to an investment capital expense that yields long-term returns.

This is a critical piece in adopting a regenerative mindset: instead of viewing soil improvement as a recurring expense that depletes the farm’s finances, we must view it as an investment that delivers continuing returns over time. We make CapEx investments in land, equipment and infrastructure; why not in remineralizing depleted soil?

As on the ledger, so in the soil: the goal of regenerative agriculture is to break free of the cycle of constant annual inputs and to make investments that result in long-term improvements.

Iodine

Now let’s turn to iodine. Iodine deficiency causes thyroid problems in cattle, just as in humans, including goiter. Iodine deficiency contributes to pinkeye susceptibility and can hamper fertility and cause birth defects. Soils across the northern United States and into Canada tend to be iodine deficient.

A common way to correct iodine deficiencies is by feeding kelp, but kelp is quite pricey. Here again, as with selenium, remediating iodine in the soil and allowing it to be given naturally to cattle through their feed is a much less expensive way to deliver iodine — and a much better long-term investment in the farm.

Human Health

The nutrient density of the food we eat has obvious consequences on human health. In particular, four nutrients have been found to be almost universally deficient in humans: selenium, iodine, magnesium and boron. Addressing these elements in our food is critical to improving the functioning of the human immune system.

Selenium is an interesting example, since it has a wide range of effects. “Prolonged selenium deficiency has been conclusively linked to an elevated risk of various diseases, including but not limited to cancer, cardiovascular disease, inflammatory bowel disease, Keshan disease, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.”2 Providing inexpensive selenium supplements to the soil can have resounding consequences all the way up the food chain.

In the spirit of producing nutrient-dense food, we must consider the most effective way to produce nutrient-dense livestock.

Data from Stephan Van Vleit of Utah State University, in partnership with the Bionutrient Institute and Edacious, shows an extremely broad range of selenium content in beef. The average selenium content of grassfed beef was measured at 16.29 mcg/110g, while grain-fed beef averaged only 2.20 mcg/110g. However the maximum selenium content of a single sample was a whopping 528 mcg/110g, while many samples had no selenium content at all.

If we want to prevent our present human health crisis at the source, we must start with the soil. Selenium and iodine are great places to begin.

A Nutritional Investment

The goal of regenerative agriculture is to improve soil health to the point where it provides all the necessary nutrients needed by crops, as well as the livestock and people who eat them. Doing so has a resounding effect: we can save money by avoiding remedial nutritional supplements to our livestock, and improve human health, by passing those nutrients up the food chain.

In adopting a regenerative mindset, we must often break free of dogmatic beliefs, like never applying soil inputs to pasture. If we zoom out and look at the full picture, such soil inputs are an incredibly worthwhile investment in the farm: they can provide lasting nutrition to livestock for years, while simultaneously improving plant and soil health, all for a reasonable price. It’s a no-brainer.